Faust Museum

The Alchemist’s Laboratory Of Doctor Faust

A journey back in time to the Renaissance:

Visit our alchemy laboratory virtually

This is how you navigate in the virtual alchemy laboratory of the Faust Museum:

By clicking on the rings, you can move around the room and zoom in on exhibits, pictures and texts.

The enlarged illustrations on the walls (16th century woodcuts) depict work in a Renaissance alchemy laboratory and the copperplate engravings show allegorical representations of chemical processes (artist: Matthäus Merian the Elder, 1593-1650).

The illustrations are taken from the alchemical work “Atalanta Fugiens”, written by Michael Maier (1569-1622), physician and alchemist.

The exhibits correspond to the materials and instruments commonly used in an alchemy laboratory in Faust‘s time. They were made available by Dr. Rainer Werthmann (Kassel), the co-curator of the alchemy exhibition, and Mr. Gerhard Zück (Faust Pharmacy Knittlingen).

In the large display case at the front of the laboratory, you can see original flasks with distilling helmets (alembics) and laboratory vessels from the 16th century that are part of the Wittenberg alchemy discovery. The digital view allows a close-up inspection that would not be possible if the display case were closed on site (these exhibits are now back at the Landesmuseum Halle).

“… this makes the Wittenberg alchemical find one of the most scientifically significant of its kind in Central Europe.”

Dr Denise Roth, Museum Director

„We have found Faust‘s laboratory!“

In 2014, the Faust Museum/Faust Archive team was visited by a delegation from the State Museum of Prehistory in Halle. Archaeologists, historians and chemists had announced themselves with a breakthrough: „We have found Faust‘s alchemy laboratory!“ Thanks to this initial contact, a wonderful cooperation with one of Germany‘s most renowned museums was born. And: through this cooperation, unique archaeological finds came to Knittlingen!

In fact, during excavations on the grounds of the Franciscan monastery in Wittenberg in 2012, the waste pit of an alchemy laboratory was discovered. It was located on the north wall of the church under a staircase and near the former monastery kitchen. Among other things, the stylistic classification of the existing utility glass suggests that it dates from around 1570 (late 16th to first half of the 17th century). At this time, the monastery had already been dissolved and the sovereign allocated the rooms for other uses. It is possible that a laboratory technician produced pharmaceutical raw materials on behalf of the prince-elector.

Since the historical Faust, Johann Georg Faust, is also presumed to have been staying in Wittenberg, the Knittlingen alchemist and mage could indeed have worked in this laboratory.

In 2015, a major conference followed on the subject of alchemy in the Renaissance in general and the Wittenberg discovery in particular. The director of the Faust Museum, Dr Denise Roth, was invited to speak about the legend-making of the Faust myth and its path to modernity and was able to use this opportunity to establish diverse contacts with colleagues and possible cooperation partners – not least with the curators and management team of the museum in Halle.

For example, an exhibit piece from the large alchemy exhibition in Halle, which opened in 2016, is at least temporarily on loan for the reconstructed alchemy laboratory in the Faust Museum in Knittlingen.

From New York to Knittlingen

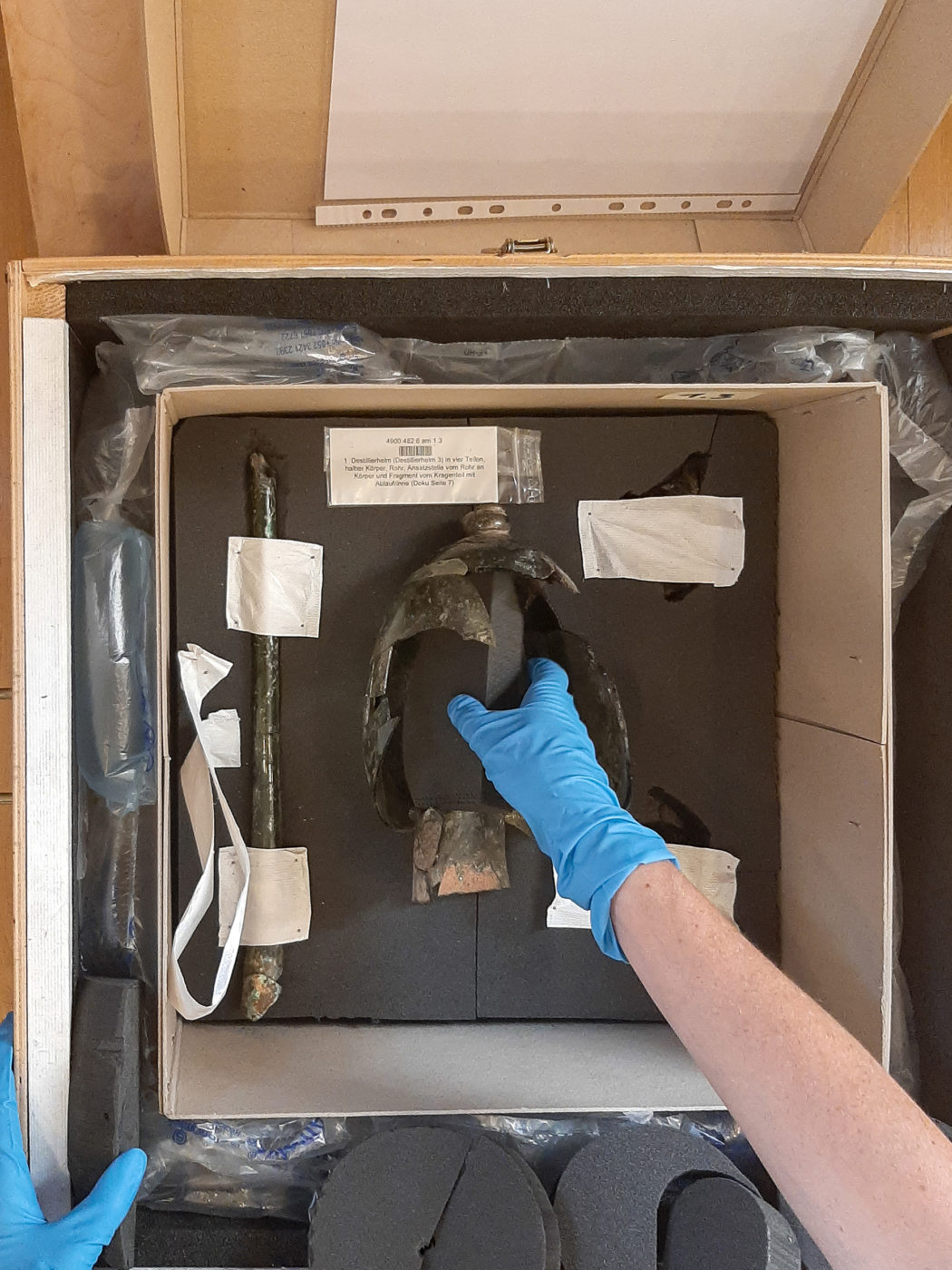

The colleagues in Halle kept their word: without much bureaucratic trouble, but with all the help that was needed, unique items made their way to Knittlingen in autumn 2020, accompanied by restorer Vera Keil, who had meticulously assembled the entire alchemy laboratory. Previously, the pieces had been on display in New York, to now make a guest appearance in Faust’s birthplace.

The discovery in Wittenberg:

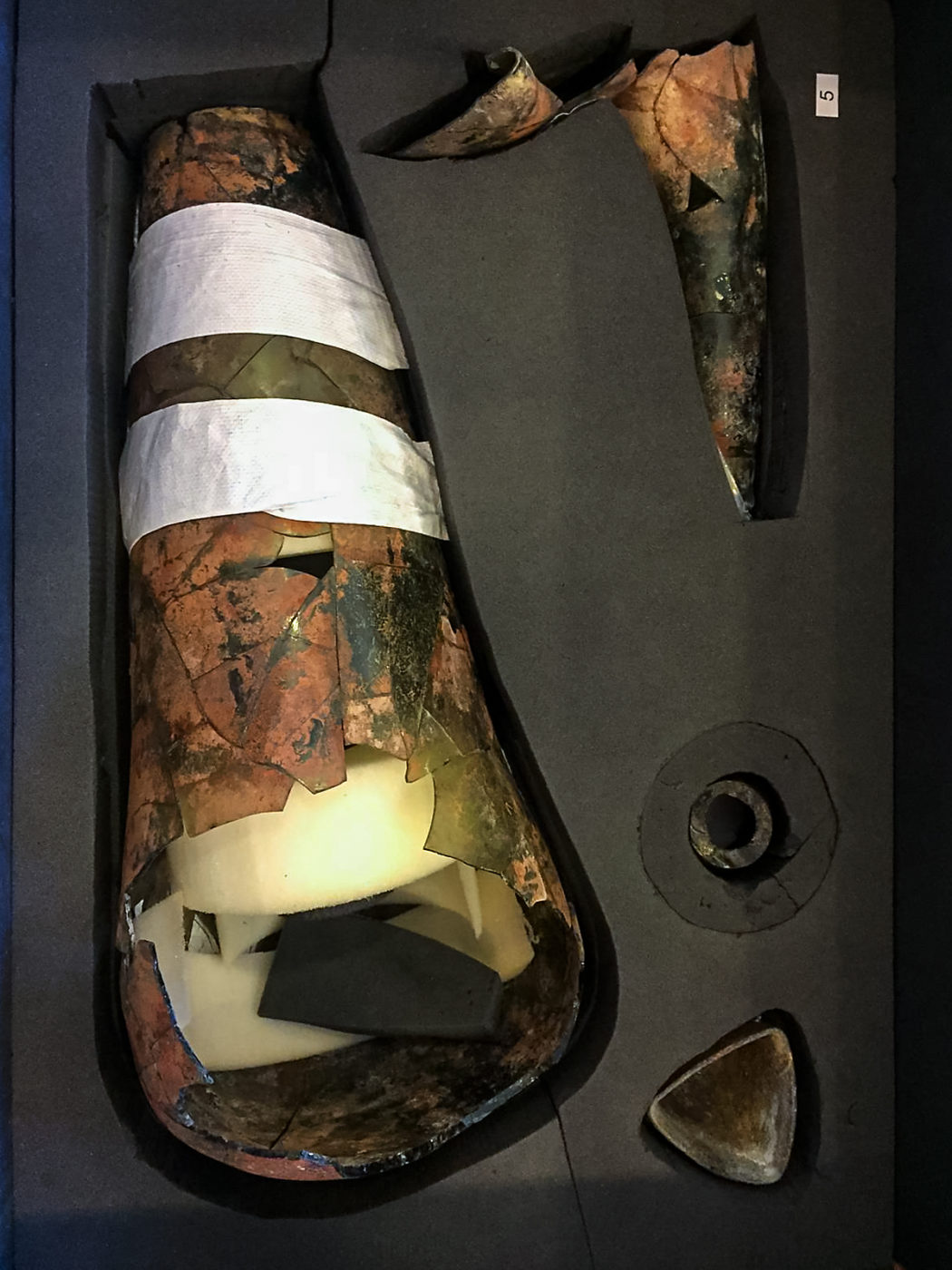

On the one hand, distinct laboratory tools made of forest glass were found, such as cucurbites (distillation flasks) in various sizes up to about 6 litres and associated distillation helmets, also called alembics, as well as crucibles made of fired clay. Retorts were made of forest glass and stoneware. An analysis of the fractured surfaces of the glasses came to the conclusion that the devices had cracked during operation and had ended up in the pit as laboratory waste. Furthermore, the pit contained household utensils that suggest a repurposing in the laboratory: a salad bowl that could be used as a sand bath, a cut-through crockery pot as a muffle, jugs, drinking glasses and a pickling jar (“sugar glass”) for storing substances.

From the residues in the flasks, retorts and crucibles, it was possible to reconstruct which substances were processed or produced in them. Apart from sulphuric and nitric acid, these were mainly antimony compounds, which had been fashionable medicines since Paracelsus. This makes the Wittenberg alchemy collection one of the most scientifically significant of its kind in Central Europe.

From the Wittenberg discovery, the display case in the Faust Museum contains a large distillation flask (so-called cucurbit) of about 5 litres capacity, a distillation helmet with a long, broken beak that roughly matches it, a retort fragment deformed by heat and a triangular melting crucible. Next to the flask lies the tip, which had been blown off the freshly produced cucurbite to best fit the opening to that of the helmet. To blast it off, one usually used a heated wire that was then wrapped around the neck of the flask at the intended place.

Background info:

The exhibit pieces cucurbit and helmet together form a distillation apparatus whose flask was heated to temperatures of a few 100 degrees at most. The cucurbit was heated from below and the vapours of the substances it contained rose up inside it to the helmet. There they cooled down and the distilled liquid condensed on the dome of the helmet. It flowed downwards into an internal channel and from there outwards via the beak, usually into a container called a condenser: a flask, a bottle or even a jug. The residues in some of the flasks suggest that nitric acid was produced with it. However, such an apparatus was also used to distil wine or produce medicines.

Retorts were used to distil high-boiling substances such as concentrated sulphuric acid. It is produced by heating roasted iron vitriol to temperatures of 700 to 800 °C and boils at over 300 °C. Due to the high temperature in the range of the softening temperature of the forest glass, the retort was visibly melted.